A Brief History of The Record Breaking Bluebird CN7 Classic Car

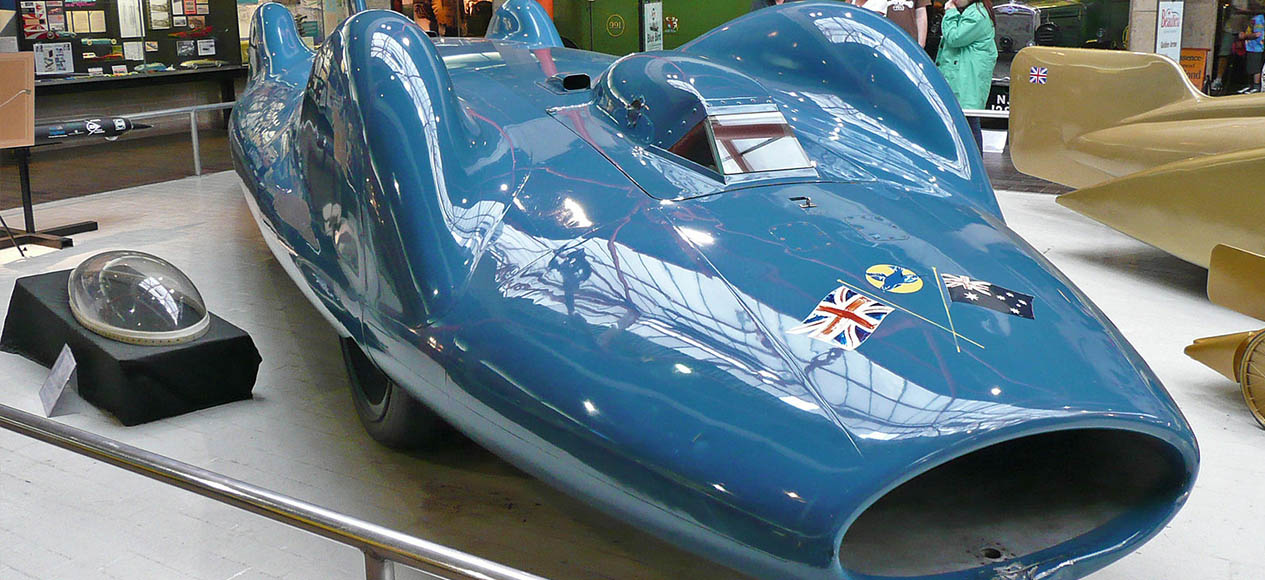

Donald Campbell’s Bluebird-Proteus CN7 was a technologically advanced classic car that truly broke boundaries. We wanted to look into the history of this land speed record-breaker, from its origins to that fateful day on Lake Eyre in Australia.

A Family Tradition

In 1956, Donald Campbell, son of Sir Malcolm Campbell, wished to keep the family tradition of holding both land speed and water speed records at the same time going. Following his water speed record success at Lake Mead, which had already earned him renowned positive acclaim, Campbell made plans to hold the land speed record (LSR) as well.At the time the record had been previously set by John Cobb, and stood at 394 mph. Campbell enlisted brothers, Ken and Lew Norris, the designers of his Bluebird K7 hydroplane, to design what was to become the Bluebird-Proteus CN7. The car was to be the best of its kind, and a spectacular showcase of British engineering, with the brothers aiming to create a car that could achieve 500 mph.Big names in the British motor industry became heavily involved in the project to build the most advanced car yet.

The New Bluebird Is Born

The car’s construction was completed in 1960 and it was to be powered by a gas turbine engine, the first successful engine of its type from the Bristol Aeroplane Company. Thanks to the specially modified free-turbine engine the car could produce over 4,000bhp.It had four wheel drive, weighed four tonnes, was built with an immensely strong aluminium honeycomb chassis, and featured fully independent suspension. It’s iconic shape was a derivative of the John Cobb built Railton Mobil Special, with an added tail fin for better stability.

Demonstrations And Setbacks

The Bluebird CN7’s first demonstration was at Goodwood Circuit in July 1960. Campbell’s machine managed to achieve a maximum of 100 mph on the straight, on just one of the laps around the circuit, due to having only four degrees of steering lock. The car was then taken to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, USA, where his father has previously broken the LSR in 1935.This record attempt, which was heavily sponsored by the likes of BP and Dunlop was unfortunately unsuccessful. Following a catastrophic crash the Bluebird CN7 was written off, with Campbell suffering some fairly severe injuries. Miraculously he survived the world’s fastest automobile accident, but his confidence was understandably shaken. He spent some time in California recovering, but by 1961 he was back planning the rebuild of the CN7 for another attempt.A rebuilt CN7 with further modifications was taken to Lake Eyre, Australia, in 1963. The location had 450 square miles of hard dried salt lake, with a 20 mile track that hadn’t seen rainfall in two decades, making it an ideal spot for the next LSR attempt. Bad luck struck and rain started to fall throughout all the test runs, becoming torrential in May. This resulted in another failed attempt with the car being removed as the lake flooded. Bad press followed and BP pulled out as a sponsor.

A Record Breaking Return

The Bluebird CN7 was returned once more to Lake Eyre by Campbell and his team, for another attempt on the salt surface in 1964. Rain was still a problem, but eventually it subsided and the surface was dry enough for a record breaking shot. The car had been designed to achieve speeds of up to 500 mph but due to the poorer surface conditions Campbell’s run was almost 100mph short of this hypothetical capability.Nevertheless, on 17th July 1964, the vehicle set the FIA world record for the flying mile at 403.10 mph. It’s been said that the car could’ve easily cracked the speeds much closer to the design maximum of 500 mph, had the track surface been hard and dry and the originally envisaged 15 miles in length. The CN7 was driven through the streets of Adelaide in celebration, there was a huge presentation at the city hall in front of a crowd of over 200,000.Sadly, Donald Campbell died during a water-speed record run in his jet hydroplane Bluebird K7 in 1967. However, he is still well recognised for his achievements, namely being the only person to achieve both the world land and water speed records in the same year. The Bluebird-Proteus CN7 classic car eventually became a permanent exhibit at the National Motor Museum, where it remains to this day.